The Hidden Limits of Release-Focused Pitching Analysis

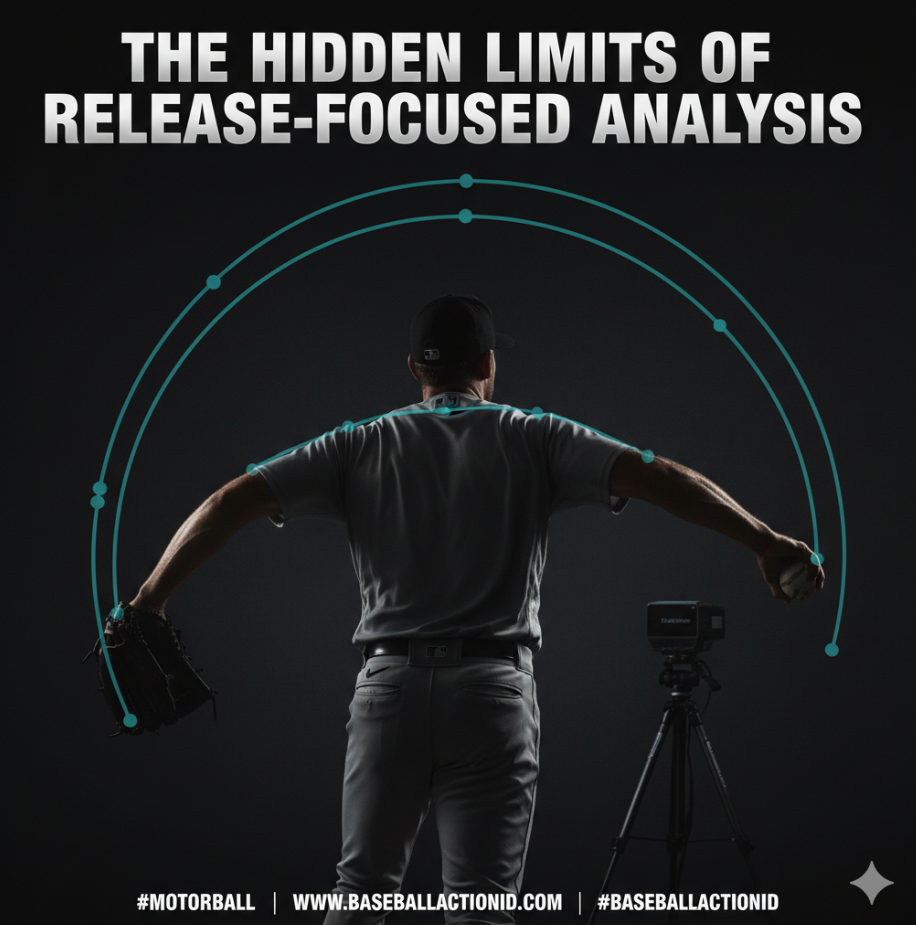

In modern baseball, technology has become the backbone of pitcher evaluation and development. High-speed cameras and advanced radar systems now dominate bullpen sessions, promising to uncover the secrets of the perfect release. On paper, it looks sophisticated — tracking release height, horizontal and vertical approach angles, spin efficiency, and more. Yet, there is a subtle danger in how this information is interpreted and applied.

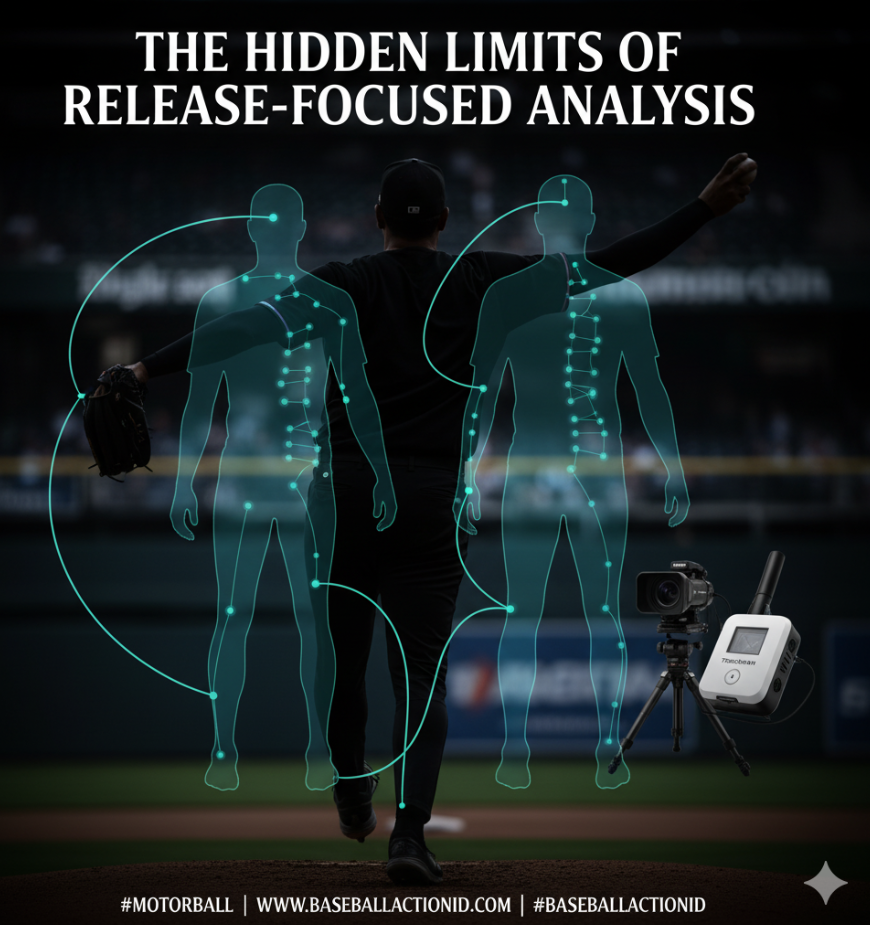

Most commonly, these systems are focused almost exclusively on what happens at the release point. Coaches and interns alike spend countless hours analysing a behind-the-scenes view, offering adjustments to grip, arm slot, or minor tweaks in release. But what about everything the pitcher does before the ball even leaves the glove? How the pitcher moves from stretch to release, the natural rhythm, timing, and individual motor preferences — these factors are rarely captured, rarely valued, and often dismissed as “noise” outside the dashboard metrics.

Here’s the subtle yet critical point:

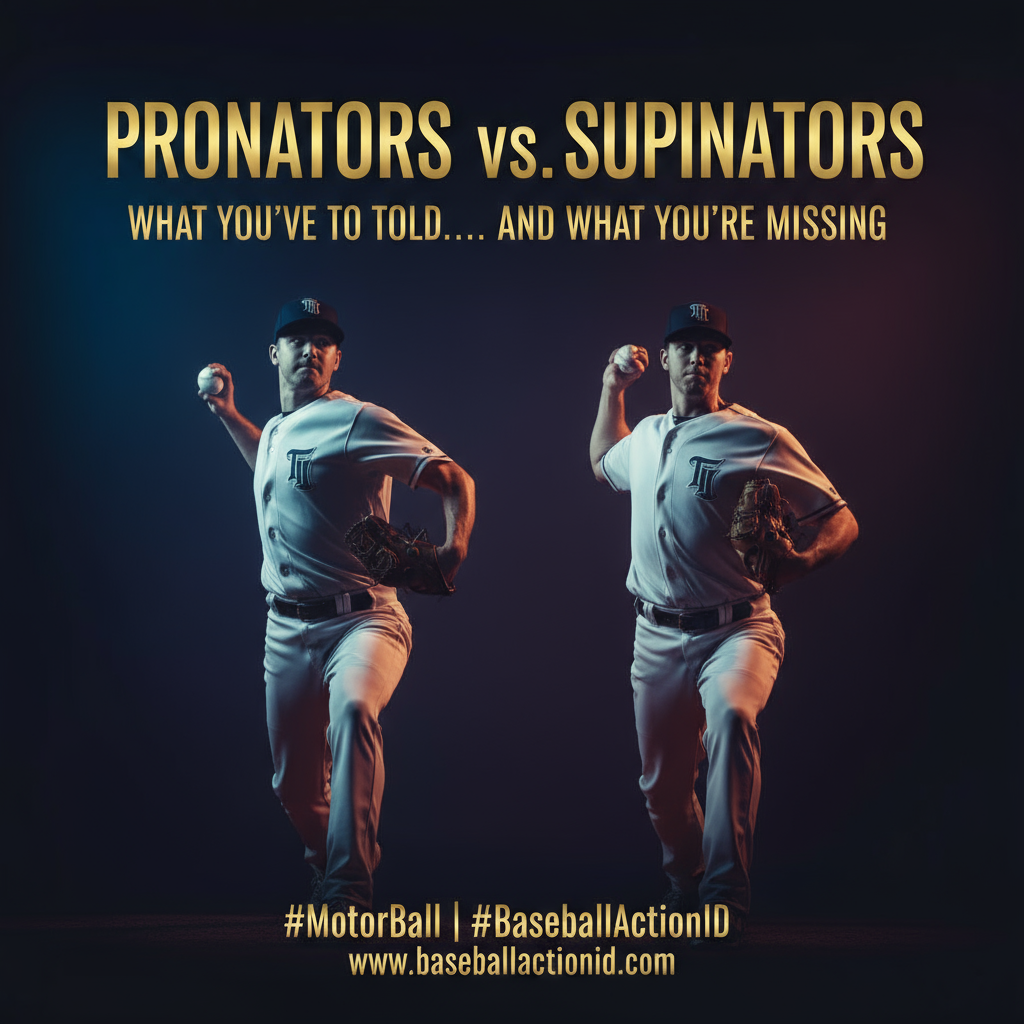

A pitcher’s tendencies toward supination, pronation, or other release characteristics are not isolated phenomena. They emerge from a deep motor preference system — a combination of global, distal, conceptual, and rhythmical preferences that shape how a pitcher naturally generates power, timing, and accuracy. In fact, supination or pronation is part of a complete blueprint of how the pitcher organises their entire body. This means that trying to analyse or “correct” supination or pronation solely by looking at release metrics is fundamentally misguided: the body will organise itself differently depending on these underlying preferences, and focusing narrowly on the release ignores the full-body dynamics that actually create these tendencies.

Attempting to “correct” release characteristics without respecting the underlying motor architecture is like tuning a Ferrari by adjusting only the tyres while ignoring the engine — the real performance comes from the integrated system, not isolated points.

This approach creates a fundamental disconnect: pitchers are coached to optimise the numbers at the point of release, often ignoring the very movement patterns that make them successful in the first place. The result is an environment ripe for misinterpretation: well-meaning but inexperienced analysts giving directions based on what the camera captures, rather than on the pitcher’s natural blueprint.

The lesson is not anti-technology!

On the contrary, high-speed cameras and Trackman data are powerful tools when used as part of a broader, preference-informed strategy. The key is contextualising what the camera sees within the pitcher’s complete motor profile. Only then can we use metrics to support development rather than impose potentially counterproductive adjustments.

The real challenge

The real challenge for MLB organisations is cultural as much as technical. Analysts and coaches must learn to balance the allure of quantifiable metrics with the intangible yet measurable patterns of natural movement. Without this balance, pitchers are at risk of subtle mechanical stress, inconsistent performance, and even injury — all while metrics may improve superficially.

Next time you watch a bullpen session, ask yourself: Are we training the pitcher, or are we training the numbers?