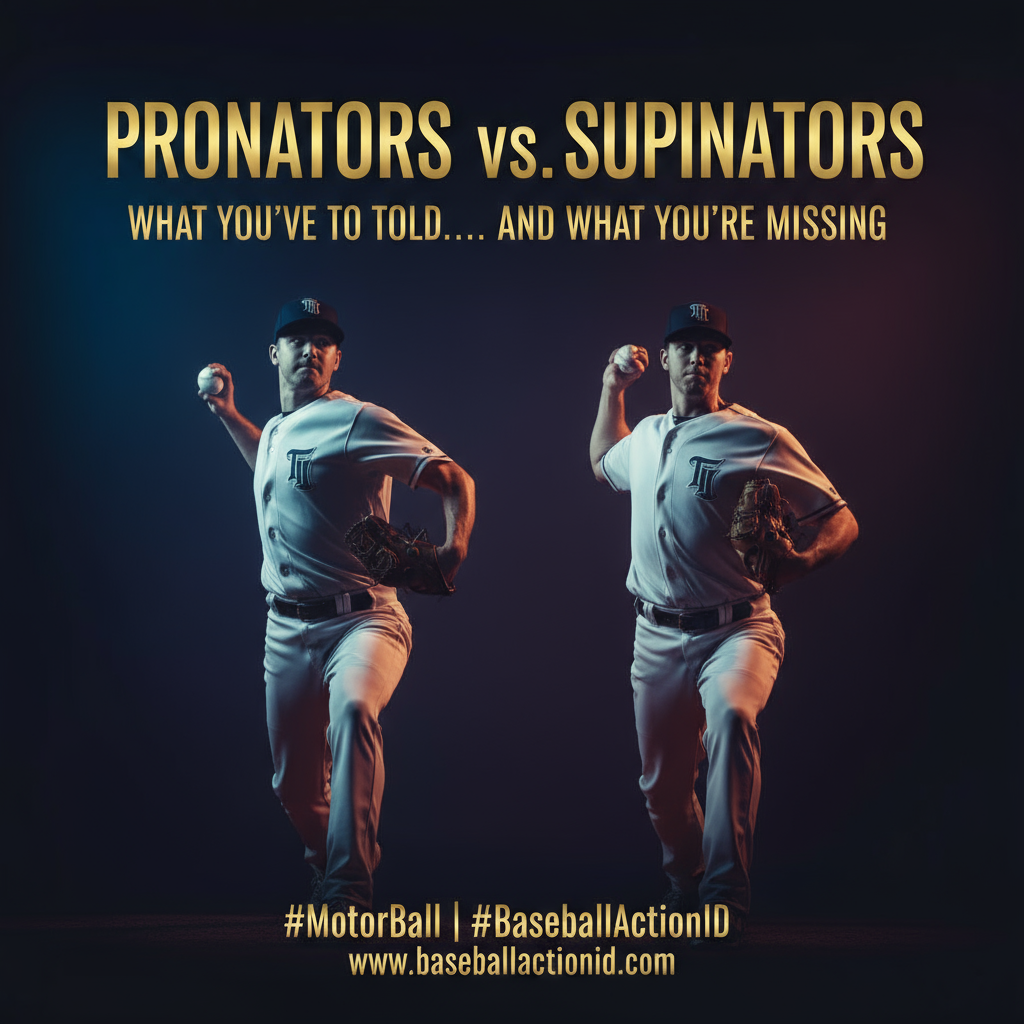

Pronators vs Supinators: What you’ve been told….And What you’re missing

Introduction

Baseball today is dominated by data. Spin rates, release points, pitch tunnelling, and biomechanical models are often presented as the roadmap to success. But there’s a fundamental misunderstanding: many of these models assume one-size-fits-all mechanics, ignoring the fact that pitchers naturally move in different ways.

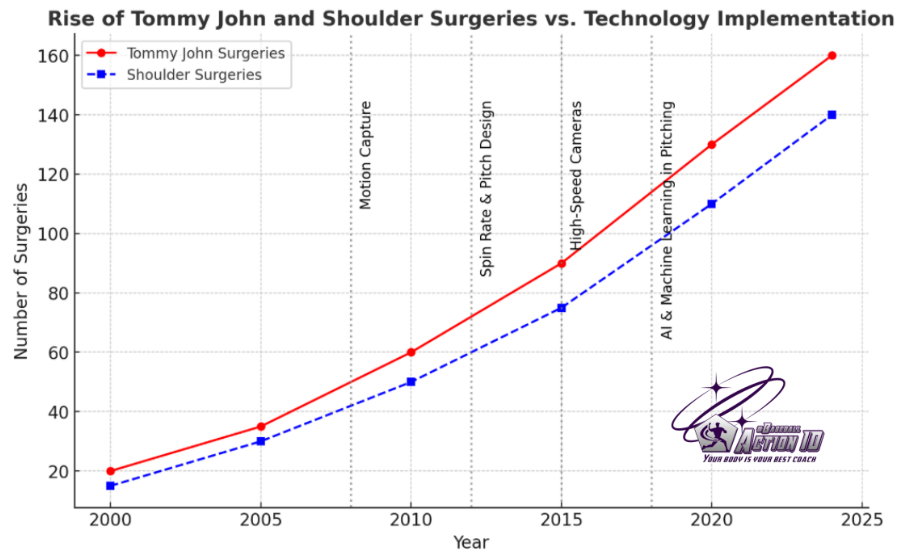

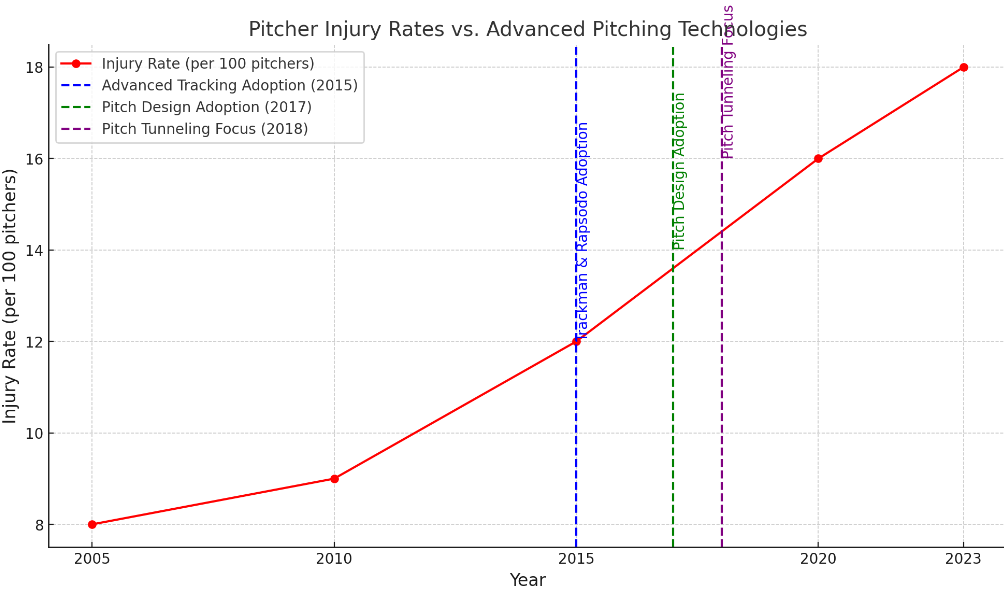

Understanding the distinction between Pronators and Supinators is key — ignoring it not only limits performance but also drives the rising injury rates in professional baseball.

What You’ve Been Told…

- Analytics and biomechanical models show the “ideal” delivery.

- If mechanics don’t match those parameters, they must be corrected.

- Uniformity in movement supposedly maximises performance and reduces injury risk.

The Hidden Danger: Pronator = The “Normal”

Today, the Pronator motion is often treated as the default standard:

Pronators: natural preference for internal rotation and strong use of the front-side kinetic chain.

Coaches, analytics models, and even scouting reports take this as the baseline for all pitchers.

The result?

Pitchers who are naturally Supinators are forced into a pattern that doesn’t fit them, leading to:

- Hidden stress on the elbow and shoulder

- Inefficient energy transfer

- Increased risk of injury

Recognising that not every pitcher is a Pronator is critical. True performance and arm health come from respecting each pitcher’s natural motor blueprint.

What You’re Missing…

Pronators and Supinators move fundamentally differently.

- Pronators rely on internal rotation and a strong front-side chain.

- Supinators rely on external rotation and a dominant back-side chain.

These differences affect every phase of the pitch — from preparation through release.

- Some voices in the pitching world do mention Pronators vs. Supinators, but they usually frame it only as a release-point difference. From there, the logic goes: “if you want to throw a certain pitch, just adjust your hand position at release.”

- That’s turning the world upside down. First, they acknowledge a natural difference — then they immediately bypass it, forcing pitchers to conform to pitch data or “standard” release norms.

- The truth is that being a Pronator or a Supinator is not just about hand position at release. It defines how the entire body coordinates during the throwing motion.

- Even if we limit the scope to the arm alone, the difference is clear from the hand break and preparation phase all the way through to the release point.

Neither style is superior.

Forcing one pattern onto the other creates hidden stress points that inevitably lead to injury.

True performance comes from authenticity.

Pitchers who throw according to their natural blueprint move more efficiently, transfer energy better, and achieve more consistent command.

Performance + Injury Prevention

Respecting natural preferences changes everything:

- Fewer injuries: no forced mechanics dictated by analytics or models.

- Better performance: pitches gain more command, movement, and confidence.

Real-World Example

A professional pitcher struggled with inconsistent results and arm soreness for years.

The only adjustment? His mechanics were aligned with his natural motor preference. Within weeks, his arm felt lighter, pitches were sharper, and performance improved.

The Pitfall of Data Alone

Spin rate, release point, and biomechanical models are valuable tools, but they don’t explain the how of each pitcher’s unique motion. Using these tools to enforce a “perfect” model ignores natural motor preferences — and that’s exactly why injuries continue to rise.

Conclusion

What you’ve been told: data and models show the perfect mechanics.

What you’re missing: every pitcher is either a Pronator or a Supinator — and only by recognising this can you maximise performance and prevent injury.

👉 Coaches, players, and decision-makers in MLB:

Use analytics as a guide, not a prescription. Identify each pitcher’s natural blueprint and train in alignment with it. That’s where the real competitive edge lies.